Across Australia, we are facing a massive shortage of specialist mathematics and science teachers, particularly in physics and chemistry. With imminent retirements and poor retention rates, this problem will only get worse. It has already reached crisis point in some areas.

This week, during his opening address at the Australia Science Teachers’ Association annual conference, Minister for Education and Training Simon Birmingham announced the federal government plans to ensure every high school has access to specialist science and maths teachers. This was also announced just prior on Channel 9’s Today Show.

While this is a noble sentiment, it’s old news. I presented on this very topic at the same conference in 2015. Since then, the issue has become worse. Fixing it will be difficult: where will we find these subject experts in the first place?

Disturbing trends

The Australian Council for Educational Research has long highlighted the supply and demand issues for science and maths teachers in Australia. About 40{fa76ff8d89001c4e403402728e1a7786cd25c7bdb58a18ff0a8051c7751c2729} of physics teachers will retire in the next 10 years but only 10{fa76ff8d89001c4e403402728e1a7786cd25c7bdb58a18ff0a8051c7751c2729} of all trainee science teachers are specialising in physics.

At least 20{fa76ff8d89001c4e403402728e1a7786cd25c7bdb58a18ff0a8051c7751c2729} of maths and physics teachers are teaching out-of-field. This is often in years 7 and 8, where developing student interest is so crucial. It’s also creeping into senior years where expertise is critical.

With a growing population, and so a growing need for more teachers, these increasing problems will accelerate further.

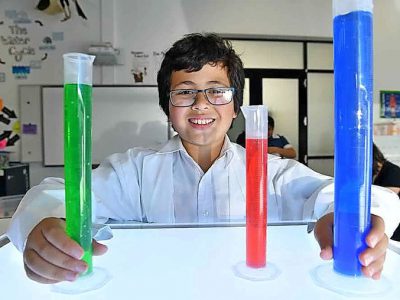

Impact on students

The increasing lack of specialist science and maths teachers is having a profoundly negative impact on students. Australia had a significant decline in scientific literacy performancebetween 2006 and 2015.

The percentage of year 12 students choosing physics declined from 21{fa76ff8d89001c4e403402728e1a7786cd25c7bdb58a18ff0a8051c7751c2729} in 1992 to 14{fa76ff8d89001c4e403402728e1a7786cd25c7bdb58a18ff0a8051c7751c2729} in 2012.

From 1999 to 2013, students choosing only the most basic level of mathematics rose from 37{fa76ff8d89001c4e403402728e1a7786cd25c7bdb58a18ff0a8051c7751c2729} to 52{fa76ff8d89001c4e403402728e1a7786cd25c7bdb58a18ff0a8051c7751c2729}.

By 2014, 21.4{fa76ff8d89001c4e403402728e1a7786cd25c7bdb58a18ff0a8051c7751c2729} of female year 12 students studied no maths at all.

Increasing inequity

These trends are Australia-wide, but impact some areas and sectors in particular. Regional and remote schools are hardest hit. These schools often fail to attract any applications for science and maths positions.

Having reached the tipping point, simple supply-and-demand economics has kicked in. Larger independent schools are relatively OK, as they can offer higher salaries, even subsidised rent.

Selective schools recruit successfully as they offer persistent intellectual rigour, with an emphasis on science and maths. Schools in beachside and lifestyle suburbs, such as Mount Eliza in Victoria, similarly fare far better with attracting staff.

That leaves the majority of non-selective government and non-selective Catholic schools plus smaller independent schools fighting over an ever-shrinking pool of specialist teachers.

The elephant in the staffroom

Schools aren’t taking this lying down. State departments of education are overtly offering scholarships. More covertly, some schools offer higher pay.

Other incentives used erratically within some schools include greater access to professional development, fewer duties, paid study leave and promotion. But increased responsibilities tend to remove specialists from the classroom.

Rather than sometimes secretive local deals, we need to accept something has to change to attract and retain specialist teachers. Current efforts are not enough.

So what else can be done?

The education establishment needs to consider a broad range of possible solutions to provide all students with access to specialist teachers. Since STEM specialists are very employable, then, yes, higher pay and financial incentives should seriously be considered to aid recruitment and retention.

For example, the UK government pledged a scheme costing A$119 million to offer school leavers a bursary to help pay for university. In return they must commit to become a teacher when they graduate with a maths or physics degree.

But we must attract the right type of person – specialists patient enough to work with kids.

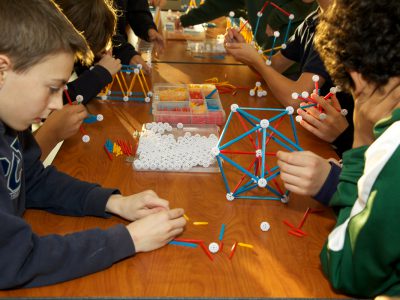

There are also other complementary strategies to consider. First, the typical model of one subject specialist (such as physics) per school is highly inefficient since only 40{fa76ff8d89001c4e403402728e1a7786cd25c7bdb58a18ff0a8051c7751c2729} of their teaching load is within their specialism (one year 11 and one year 12 class).

Such experts could be coordinated to work across multiple schools. Technologies such as video conferencing and collaborative online spaces should be better leveraged to increase the reach of experts to students, be they geographically remote or simply lacking specialist teachers.

Secondly, the sheer volume of retirements must be stemmed. Mechanisms need to be created to encourage gentler retirements, allowing specialists to maintain senior classes without all the usual hassles, admin and stress. With changes to the science and maths curricula, we can’t afford to lose such expertise all at once.

What next?

Now the shortage of specialist science and mathematics teachers has been raised politically (though somewhat belatedly), we need to see a proper plan of action, otherwise they are empty words. But for those brave enough to truly tackle the problem, there are solutions out there.