As the Morandi Bridge collapse in Genoa demonstrated, ageing infrastructure is an alarming problem facing the developed world.

We need engineers to maintain this infrastructure, largely built in the post-war period and coming to the end of their design lifespans. At the same time, cities are racing to build urgently needed infrastructure to accommodate rapidly growing urban populations.

In their 2017 report Engineers Make Things Happen, Engineers Australia states that Australia is over-dependent on skilled migrants to fill engineering roles.

To remedy this, they reinforce the well-recognised need for more students to study STEM subjects like advanced maths and physics in order to ‘build the necessary technical educational foundation for Australia’s innovation revolution.’

They have the right idea, but how do we realistically make it happen?

Given that the same report highlights the shockingly low numbers of Year 12 girls enrolled in advanced maths and physics, the subjects underpinning all engineering practice, we clearly need to find new ways to get all students, boys and girls, to care about studying STEM.

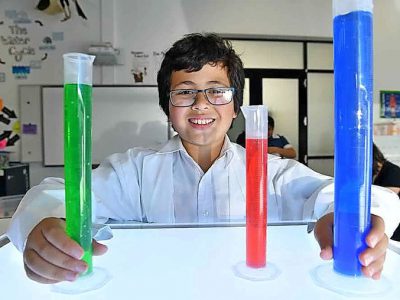

Perhaps we need to give them a better incentive? In our schools, students study science, technology and maths, but we don’t teach them how to apply these skills creatively to solve problems in the real world. Care about building a safe and sustainable city? Want to fix global issues like clean water and climate change? You can use maths and science to solve these problems creatively.

It’s called ‘engineering’.

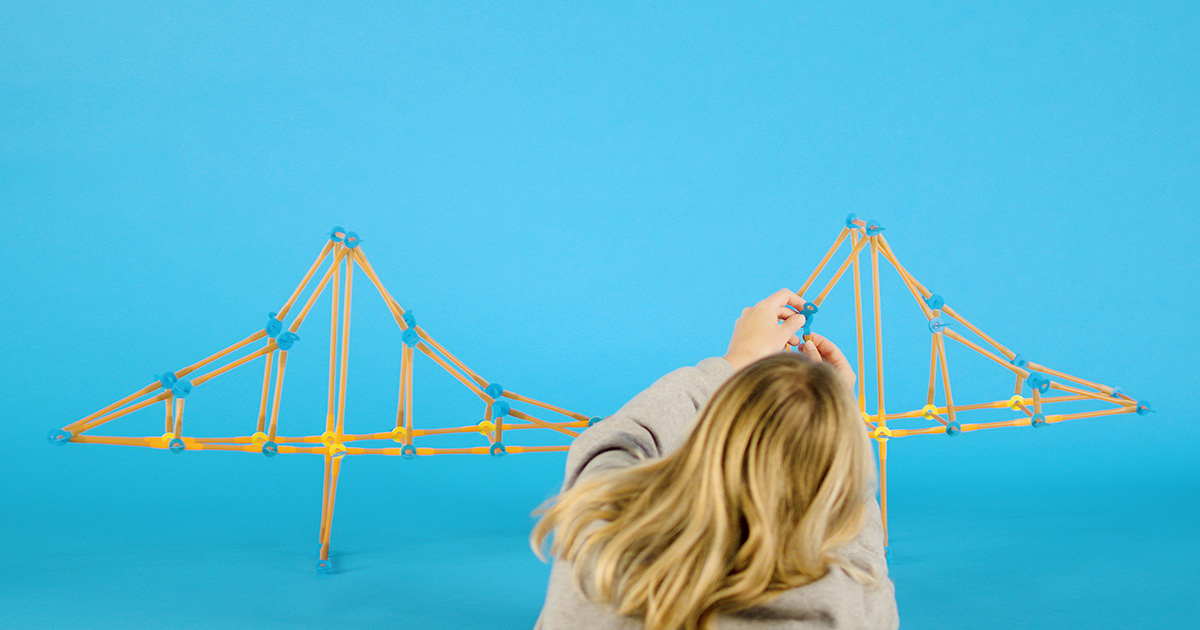

Engineering is the glue that holds STEM together. It turns the theory into practice. Just as there are specialist art, music and foreign language teachers, we need specialist STEM teachers to show how maths and science can be creatively applied.

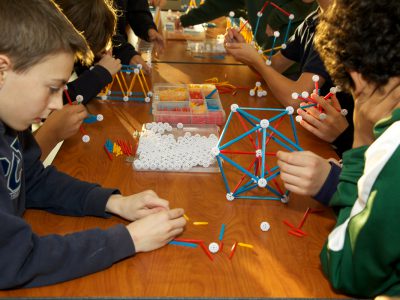

Education systems need to take this need seriously if we’re ever to address our critical infrastructure needs, and leaving it too late in the curriculum will no longer do. Primary schools are the breeding ground for the careers of the future. We need to start there.

A specialist STEM teacher is even more critical for our girls. If we’re committed to increasing the amount of women in engineering from the 13 percent currently practising in Australia, we’ve got to work much harder to involve them from the start.

Currently, most girls don’t encounter engineering until very late. With no specialist STEM teacher to introduce the foundational ideas and practices early, and with few role models to show they belong in the modern engineering workplace, why would we expect them to invest in studying the maths and science subjects they need for a career in engineering?

It becomes far more possible though if we teach girls that their STEM skills can create solutions to local and global problems that make a real difference to people’s lives. If we helped them make this leap, Australia’s technology future would be far more assured.

We need a healthy and balanced team of both men and women on board to come up with the best ideas. This is why STEM education, with a focus on applying maths to a creative design process, needs to be part of our curriculum.

To do this, a long and well-argued position includes supporting teachers to build their skills in teaching maths and science so they can help our students become creators of technology, rather than simply users.

Initiatives abound, but they are always short-term projects that finish abruptly with cuts to funding and support.

Educational success isn’t measured in the short cycles of elections; it is measured in the long-term developments of students’ attitudes, skills and expectations of themselves, their future work and the shape of their nation.

During World War II, Rosie The Riveter showed the world how much society benefited when women were invited to contribute as engineers. They ran factories, built aircraft and kept industry open for business. Our infrastructure needs are as enormous now as they were 70 years ago.

With our proportionally tiny population in the region, we need more engineers to build the type of technologically innovative economy we need to maintain our living standards.

Let’s start by recruiting them first into our primary school classrooms. STEM education offers a way of doing that, and it’s time for education systems to take it seriously.

With more home-grown engineers on our team, women included, we’ve got the best chance of coming up with the right solutions to keep Australia smart, sustainable and competitive.