Top colleges boast about reaching gender parity in ‘intro to computer science’ courses. But very few of those women go on to graduate with a CS degree. Here’s why.

The classrooms at Georgia Tech, among the laptops and notebooks and lines of code, senior computer science major Marguerite Murrell likes to play a game she’s dubbed “Count the Girls.”

“If I can keep it under two hands, then I win,” Murrell said. “There are certainly some girls, probably more than some other computer science programs in the nation. But it’s a lot of guys.”

Women earn only 18% of computer science bachelor’s degrees in the United States. And leaders such as Apple CEO Tim Cook have stated that if the US tech industry doesn’t solve its gender imbalance issues then America will lose its lead in tech.

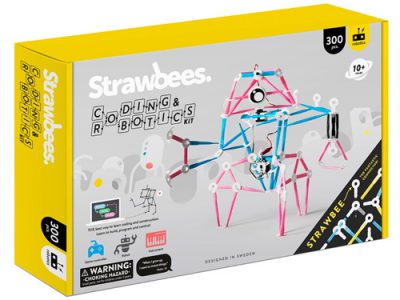

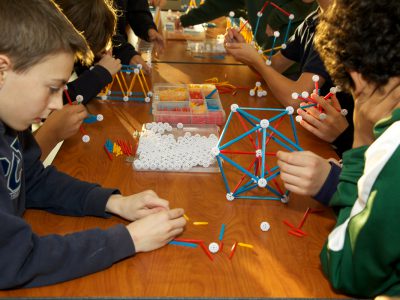

But in recent years, a number of top colleges have made efforts to draw women into the field with revamped introductory courses that make the technology less intimidating for those that enter college without prior programming experience—largely, women—among other efforts. Many of these schools boast about gender parity in these basic courses and incoming freshman classes. But for upper-level students, men continue to dominate technical courses in robotics, machine learning, and security, and “Count the Girls” still yields poor results in those classes.

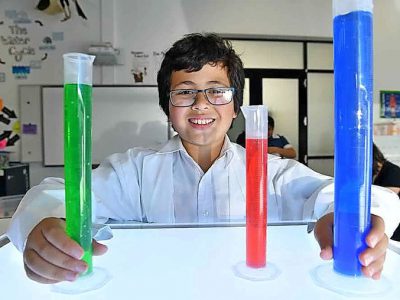

A confluence of factors prevent women from pursuing and persisting in computer science majors, according to Wendy DuBow, director of evaluation and senior research scientist at the National Center for Women & Information Technology. A lack of exposure to computer science and engineering concepts in middle school and high school, well-meaning teachers or parents steering girls away from tech-focused classes, and a general lack of awareness of potential careers in the tech field all contribute.

Recent high-profile sexual harassment cases at tech firms such as Uber also do not make the field appear as an attractive place for women to build a career, DuBow said, no matter how lucrative.

Carnegie Mellon University, Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Harvard University, Stanford University, University of California-Berkeley, and Georgia Institute of Technology have all made a concerted effort to attract female students to computer science programs.

“Academic institutions that commit to parity really do start to see results when they use research-based practices, like scaffolding their intro courses or making sure their faculty use inclusive pedagogy in the classroom,” DuBow said. However, challenges with isolation, stereotyping, and confidence still remain.

What follows is a look beyond the glossy college catalogues into what female computer science majors actually experience on campus, and why changing introductory courses isn’t enough to build the pipeline of women needed to fill tech jobs.

Progress made, work ahead

Many colleges recognize that the way their computer science programs were structured discouraged women from entering, said Elizabeth Ames, senior vice president of marketing alliances and programs for the Anita Borg Institute. For example, entry-level courses often assumed that students had a background in programming already. And, women in tech had little community on campus.

The oft-named success story of changing this approach is found at Harvey Mudd College in Claremont, CA, where the percentage of female computer science majors grew from less than 15% in 2016, largely thanks to the initiatives put in place by its president Maria Klawe.

Carnegie Mellon University has seen similar results: Women made up more than 48% of incoming freshman in the computer science major in 2016-17—a far cry from 8% in the 1990s, and even 34% in 2013. Many of the changes were spurred by Lenore Blum, a professor of computer science who joined the faculty in 1999.

Her guiding philosophy? “The minority in any community does not have the same access to the critical academic and professional opportunities and advantages that the majority has, and these are critical for success,” Blum said. For example, male computer science majors have easy access to role models who look like them, in both their professors and people in the workforce, and are more likely to have roommates or people living in their dorm who are also studying computer science and can help with homework.

“If you’re a woman, and one out of a very small number, you don’t have those built-in connections, and your teachers don’t look like you,” Blum said. “You have nobody to ask naturally at night to work on homework with you. It would probably be pretty awkward to call up a guy and say, ‘Hey, I’m having problems with my homework and it’s midnight. Want to come over?’ Not so easy to do.”